The UK Supreme Court has ruled that the terms ‘man’, ‘woman’ and ‘sex’ in the 2010 Equality Act refer to biological sex.

The case followed a legal challenge by the anti-trans campaign group For Women Scotland over who counts as a woman in legislation intended to increase the number of women serving on public boards. The Scottish Government’s approach was inclusive of trans women who hold a Gender Recognition Certificate – a category that FWS wished to redefine.

Categories used by the state to sort people into boxes – according to shared characteristics – are never neutral. Rather, the number of boxes available and the borders of categories are always contingent on who is in charge. The design of sex and gender categories is therefore not some dusty topic reserved for administrators and bureaucrats – it has become the main battlefield for trans equalities in Scotland and the UK.

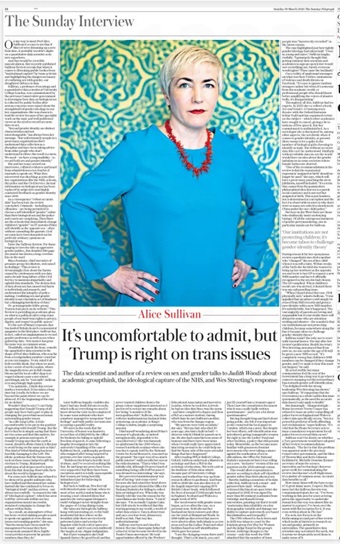

The court case is the latest ‘gender critical’ effort to narrow sex and gender categories in policy, data and law so that they record trans, non-binary and queer people in ways that go against how they wish to identify. Other examples include the wording of the sex question in the recent census and Professor Alice Sullivan’s recent review of sex and gender data.

Common-sense categories

These ‘gender critical’ interventions evoke an imagined past when sex and gender categories were common-sense. As Sullivan writes in her review, ‘The term “sex” has lost its ordinary meaning in data collection’ harking back to a time when organisations like the Office for National Statistics and the Government Statistical Service presented sex ‘as an ordinary and uncomplicated core demographic characteristic’ – simpler times before trans people got in the way.

The ordinariness of sex as a category echoes Donald Trump’s recent Executive Order that affirms the ‘biological truth’ of two sexes and defends ‘the ordinary and longstanding use and understanding of biological and scientific terms’.

There should be nothing ‘ordinary’ about the embrace of a Trumpian approach to sex and gender in UK policy conversations – it is an alarm bell!

Because what campaign groups like FWS are demanding is not a continuation of the recent past – where legislation such as the Gender Recognition Act (2004) and Equality Act (2010) offer protections to trans people in law – but a sharp handbrake-turn that strips trans people of the categories they use to describe themselves and forces them into boxes not of their choosing.

Let’s be specific about who exactly will be impacted by a legal change in the relationship between sex and gender: trans people. In Scotland, according to the 2022 census, this community totals around 19,000 adults or 0.44 per cent of the population (with just 3,090 individuals identifying as trans women – the focus of the Supreme Court case).

Useful categories

So is there anything we can all agree on? A common principle to guide us through contested categories? Perhaps the need for clarity in terms of what sex and gender categories mean and who they include and exclude? A standardised approach with clear rules that apply in all situations? An approach to categories that is less complicated?

Well – the world that we inhabit is complicated. Its messy and its fluid. For some people, describing their sex and/or gender feels like pinning jelly to the wall. So why would the categories used in legal and data systems to represent these experiences be any different? Calls for ‘coherency’ or to tidy the smudged lines of a category are never as innocent as they might first appear, particularly when those located at the edges of categories find themselves tipped into boxes not of their choosing.

Rather, what we need are useful categories that work for the decisions being made. In the example of the Scottish Government’s initiative to boost the number of women on public boards, it makes sense to use a definition of sex that best serves the purpose of maximising the number of women boards. It’s not rocket science.

Surely this contextual approach is more appropriate than a sweeping definition – ordained from above – that is crude, exclusionary and advances a fiction that assumes everyone’s lives can (and should) map directly to clear categories with discrete boundaries.

In his account of how US government agencies classify individuals as ‘male’ and ‘female’, political scientist Paisley Currah argues that classification criteria depend on what a particular agency does – coining the aphorism ‘sex is as sex does’. For example, sex classification rules differ when they relate to the regulation of marriage, property law, prison populations or the security of air travel.

This flexibility does not suggest that each government department must devise a bespoke definition of ‘sex’ but surely this contextual approach is more appropriate than a sweeping definition – ordained from above – that is crude, exclusionary and advances a fiction that assumes everyone’s lives can (and should) map directly to clear categories with discrete boundaries.

A hollow form of inclusion

A likely fallout from today’s ruling is the announcement of further government reviews into ‘conflicts’ between sex and gender categories in law, policy and data. This path forward will not help anyone.

We do not need more reviews that force trans people to provide proof of their existence – that ask them to turn up and engage in dialogue alongside anti-trans campaigners calling for their erasure. As feminist scholar Sara Ahmed writes in her essay An Affinity of Hammers, ‘an existence can be nullified by the requirement that an existence be evidenced’.

Reviews of sex and gender categories facilitate the demands of anti-trans campaigners as they offer institutional platforms for a small (but extremely loud) cluster of activists to share their opinions alongside evidence from scientists, statisticians and legal experts. But in the process – in this search for evidence – we end up inventing problems that do not really exist. What follows are the publication of weighty reports detailing comprehensive lists of solutions all in search of a problem.

Another possible development – already being championed by ‘gender-critical’ campaigners – is the proposal that alongside a more restrictive ‘sex’ category (exclusively based on a person’s biological sex at birth) we should also include an additional category of ‘gender identity’.

In the context of UK policy and data practices, the addition of a ‘gender identity’ category is insufficient – it’s a hollow form of inclusion because the category of ‘sex’ is positioned as the default approach, with ‘gender identity’ an exotic add-on for individuals who wish to describe themselves in weird and wonderful ways.

In my new book, I describe this charade of inclusion as a rainbow trap: the requirement to put yourself into a category not of your choosing. Yes – you are included, but on someone else’s terms. For example, the most recent round of UK censuses forced all respondents to answer a binary sex question but then – in a subsequent question on trans/gender identity – offered respondents the opportunity to identify as non-binary.

This is the trap being laid out in front of us. Queer people are being sold a poor version of inclusion and any refusal to jump through the hoops on offer (as decided by partisan figures such as ‘gender critical’ academic Alice Sullivan) mean that these communities are then positioned as a problem.

As a result, when trans people (understandably) refuse to define themselves according to their sex at birth – particularly when this has no relevance to the topic under investigation – they are reframed as the ones being difficult.

Fuck this. It’s wrong. It’s using the language of inclusion to advance a more restrictive and exclusionary approach to categories than what came before. The politics of categories exposes competing visions of the world – with ‘gender critical’ campaigners keen for their version of sex and gender to trump all others.

Top-down efforts to establish watertight rules for sex and gender – that work across all possible contexts – never succeed. All they achieve are making life more difficult for the small number of individuals who find themselves assigned to a box that does not reflect who they are or their experiences.

Kevin Guyan is the author of Rainbow Trap: Classifications, Queer Lives and the Dangers of Inclusion (Bloomsbury Academic, 2025), which is available to preorder.

Leave a comment