I finished my presentation and opened the floor to questions from the audience. One hand quickly shot up. The person clasped the microphone and shared their struggle of trying to get their employer to adopt more inclusive approaches to gender, sex and sexuality data. Every head in the room nodded in agreement.

Book events are often quite formulaic and tend to follow a standard format: short intro, perhaps a reading, followed by a Q&A striking the right balance of intellectual insights and witty one-liners. Where things get most exciting is when the microphone passes from the author to the audience, and anything can happen.

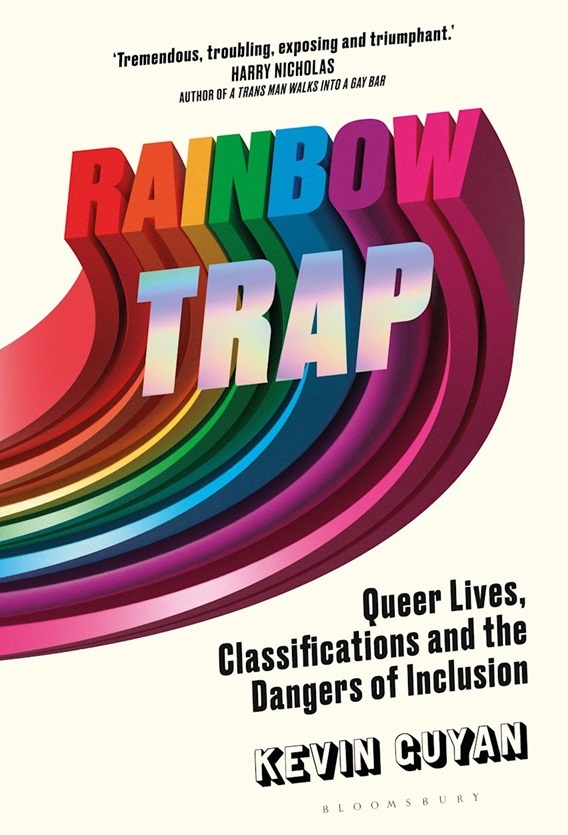

Since the publication of Rainbow Trap in June 2025, which explores the data categories assigned to LGBTQ communities, I’ve spoken at several in-person and online events across the UK. What has become clear to me is a distinction between writing a book and speaking about a book. While the former is predominantly a solitary task, the latter is a call-and-response that lets authors know (through groans, giggles and gasps) what ideas resonate and what ideas fall flat.

Based on questions asked by audiences, conversations that followed and subsequent messages on social media, here is my list of ten things I have learnt about LGBTQ data since publishing a book all about LGBTQ data.

1. The LGBTQ data debate has changed

In the UK, the relationship between LGBTQ communities and data has transformed radically during the past decade. I sometimes think back with disbelief that in the mid-2010s serious conversations were taking place about including a non-binary sex question in the national census! Now, in 2025, we’re fighting efforts to undo inclusive approaches to data and install a biology-first approach to gender, sex and sexuality in law, policy and data practices.

2. Data and the anti-trans playbook

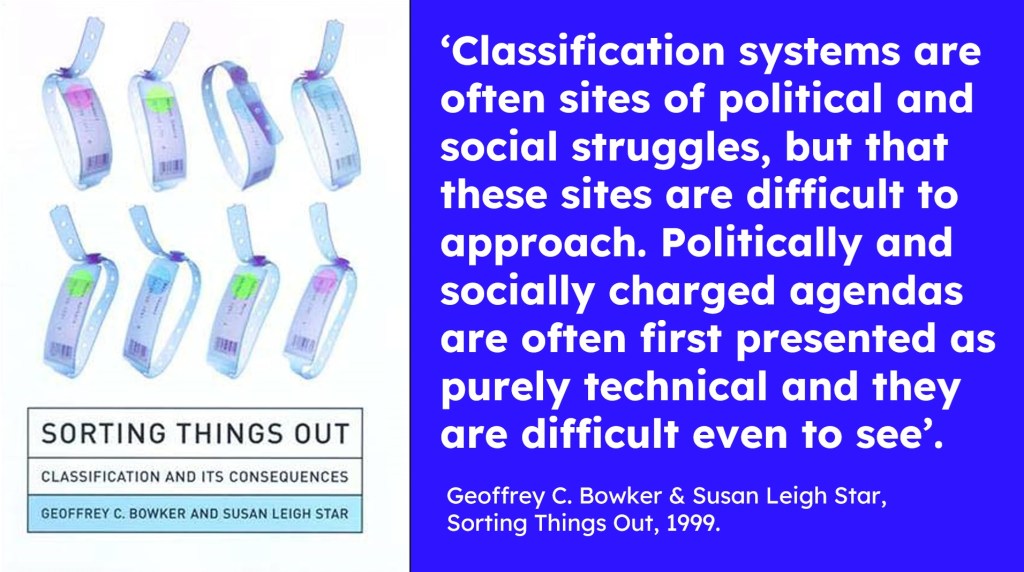

Anti-trans campaign groups have known exactly where to target their time, energy and resources – the design and definition of ‘sex’ in seemingly mundane administrative policies and systems.

Examples include Fair Play for Women’s successful legal challenge against the Office for National Statistics and the guidance that accompanied the sex in the 2021 English and Welsh census (which has since had trickle-down effects across all data practices) and Sex Matters unsuccessful attempt to add amendments to the Data (Use and Access) Bill (2025) encoding a biological definition of ‘sex’ in law.

3. The politics of evidence

There is a widespread scepticism as to how change happens and the role that evidence plays in this process. Audiences queried the power of evidence, such as numerical data about LGBTQ lives, to change the hearts and minds of decision makers. This scepticism reflects a loss of faith that research findings or a compelling dataset can single-handedly shift conversations in ways that meaningfully improves the lives of LGBTQ communities.

4. The people behind the numbers

Audiences were itching to speak about the people behind the numbers – not just LGBTQ communities about whom data is collected but also the people responsible for collecting, analysing and using this data.

For many individuals, these two worlds overlap as they both identify as LGBTQ and work in a job that involves LGBTQ data. Queer data workers shared feelings of rage when trying to improve data practices but kept bashing into brick walls or felt complicit when data about LGBTQ communities was mainly used to justify tokenistic DEI initiatives.

5. Who’s in the room?

Relatedly, audiences asked about the experiences and expertise of the people making decisions about LGBTQ data. Too often, in my work, I have seen individuals assigned to lead major reviews of gender, sex and sexuality data who know next to nothing about the topic under investigation (and, even worse, they don’t know how little they know). How can we ensure the right people are in the room?

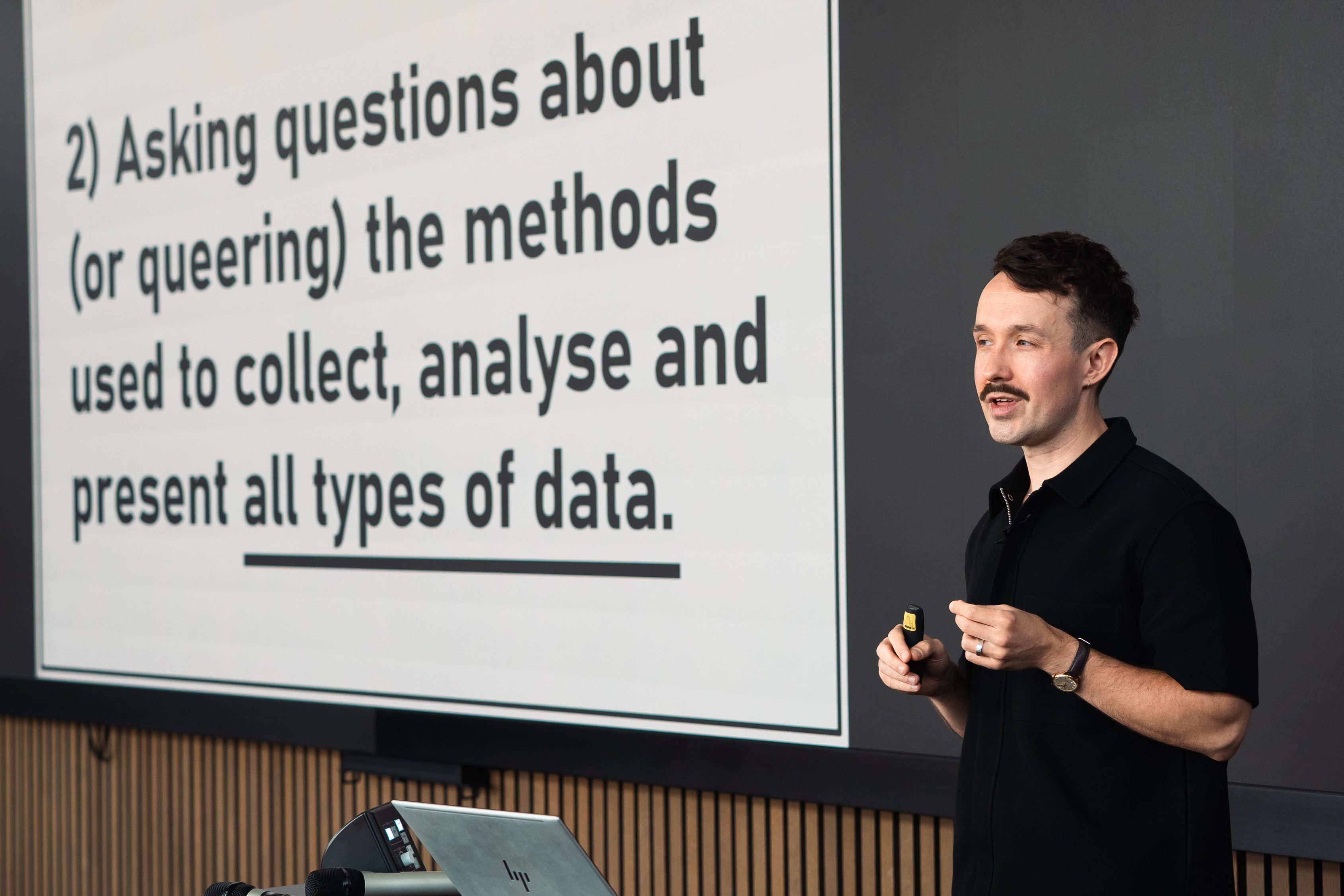

6. Old theories, new applications

Many of the concepts we discussed (e.g. intersectionality, the social construction of identities, looping effects) are not all that new – some have been hanging around academic and activist circles for over thirty years! What is new is retooling these concepts and applying them to contemporary LGBTQ data issues such as diversity monitoring, generative AI, consent and refusal.

7. Diversity monitoring forms

People love speaking about diversity monitoring forms. Perhaps it is the collective experience of starting a new job or registering with an organisation and being asked questions about your gender, sex and sexuality that fail to reflect who you are. As a method, it is clear that a two-dimensional list of nine stand-alone questions is broken and audience members were keen to share creative alternatives (including the use of AI and virtual reality!)

8. Adding more categories is not enough

A point that everyone seemed to agree on was adding more response options to forms collecting data about gender, sex and sexuality did not – on its own – address structural and systemic problems in data systems. For example, expanding the number of sexuality options might help address historical exclusions but you are still inviting people into a data system that was not previously fit for purpose.

9. Identity data is ‘too messy’

There exists a mood – across several government departments and agencies – that data about people’s identity characteristics is too messy. In response, audiences highlighted a slew of initiatives trying to standardise and harmonise approaches to gender, sex and sexuality data.

While buzzwords associated with these projects all sound promising – ‘quality’, ‘accuracy’ and ‘interoperability’ – efforts to standardise and harmonise data risk making things worse and overlooking the many queer lives that fall between categorical cracks.

10. How do we speak about data without ‘talking the talk’

The use of data, more so than the collection or analysis of data, came up a lot during audience interactions. In particular, we explored how we communicate data without falling into the trap of ‘talking the talk’.

We all know the temptation: splash a headline stat, dazzle your audience with charts and stay clear of complexity. But these approaches flatten stories and elevate certain types of data. Is it ever possible to make an impact with data without playing by pre-established rules of the game?

I hope it never stops feeling like a strange experience. People taking time from their day to listen to me (!) speak about a topic that I am passionate about. But it’s a passion shared with others – and these opportunities to engage in conversations refine my thinking about the topic and hopefully help others think critically about gender, sex and sexuality data.

Kevin Guyan is the author of Rainbow Trap: Classifications, Queer Lives and the Dangers of Inclusion (Bloomsbury Academic, 2025) and Director of the University of Edinburgh’s Gender + Sexuality Data Lab.

Leave a comment